How Codeflash measures code runtime

Codeflash reports benchmarking results that look like this:

⏱️ Runtime : 32.8 microseconds → 29.2 microseconds (best of 315 runs)

To measure runtime, Codeflash runs a function multiple times with several inputs and sums the minimum time for each input to get the total runtime.

A simplified pseudocode of Codeflash benchmarking looks like this:

loops = 0

min_input_runtime = [float('inf')] * len(test_inputs)

start_time = time.time()

while loops <= 5 or time.time() - start_time < 10:

loops += 1

for input_index, input in enumerate(test_inputs):

t = time(function_to_optimize(input))

if t < min_input_runtime[input_index]:

min_input_runtime[input_index] = t

total_runtime = sum(min_input_runtime)

number_of_runs = loops

The above code runs the function multiple times on different inputs and uses the minimum time for each input.

In this document we explain:

- How we measure the runtime of code

- How we determine if an optimization is actually faster

- Why we measure the timing as best of N runs

- How we measure the runtime when we run on a wide variety of test cases.

Goals of Codeflash auto-benchmarking

A core principle of Codeflash is that it makes no assumptions about which optimizations might be faster. Instead, it generates multiple possible optimizations with LLMs and automatically benchmarks the code on a variety of inputs to empirically verify if the optimization is actually faster.

The goals of Codeflash auto-benchmarking are:

- Accurately measure the runtime of code

- Measure runtime for a wide variety of code

- Measure runtime on a variety of inputs

- Do all the above on a real machine, where other processes might be running and causing timing measurement noise

- Finally make a binary decision whether an optimization is faster or not

Racing Trains as an analogy

Imagine you're a boss at a train company choosing between two trains to runs between San Francisco and Los Angeles. You want to determine which train is faster.

You can measure their by timing how long each takes to travel between the two cities.

However, real-life factors affect train speeds: rail traffic, unfavorable weather, hills, and other obstacles. These can slow them down.

To settle the contest, you have a driver race the two trains at maximum possible speed. You measure the travel times between the two cities for each train.

Train A took 5% less time than Train B. But the driver points out that Train B encountered poor weather, making it impossible to draw firm conclusions. Since it's crucial to know which train is truly faster, you need more data.

You ask the driver to repeat the race multiple times. In this scenario, since they have plenty of time, they repeat the race 50 times.

This gives us timing data (in hours) that looks like the following.

With 100 data points (50 per train), determining the faster train becomes more complex.

The timing data contains noise from various factors: other trains on the tracks, changing weather, and so on. This makes it challenging to determine which train is faster.

Here's the crucial insight: timing noise isn't the train's fault. A train's speed is an intrinsic property, independent of external hindrances. The noise only adds time—there's no "negative noise" that makes trains go faster. Ideally, we'd measure speed with no hindrances at all, giving us clean, noise-free data that shows true speed.

In reality, we can't eliminate all noise. Instead, we minimize it by focusing on the "signal"—the train's intrinsic speed—rather than the noise from hindrances. By running multiple races, we get multiple data points. Sometimes conditions are nearly perfect, allowing the train to reach maximum speed. These minimal-noise runs produce the smallest times—our "signal" that reveals the train's true capabilities. We can compare these best times to determine the faster train.

The key is finding each train's minimum time between cities—this closely approximates its maximum achievable speed.

How Codeflash benchmarks code

This principle of measuring peak performance while minimizing external noise is exactly how Codeflash measures code runtime. Computer processors face various sources of noise that can increase function runtime:

- Hardware: cache misses, CPU frequency scaling, etc.

- Operating system: context switches, memory allocation, etc.

- Programming language: garbage collection, thread scheduling, etc.

Codeflash minimizes noise by running functions multiple times and taking the minimum time. This minimum typically occurs when there are fewest hindrances: the processor frequency is maximal, cache misses are minimal, and the operating system is not doing context switches. This approaches the function's true speed.

When comparing an optimization to the original function, Codeflash runs both multiple times and compares their minimum times. This gives us the most accurate measurement of each function's intrinsic speed which is our signal, allowing for a meaningful comparison.

We've found that running a function multiple times increases the likelihood of getting these "lucky" minimal-noise runs. To maximize this, Codeflash runs each function for 10 seconds with a minimum of 5 loops, balancing measurement accuracy with reasonable runtime.

What happens when there are multiple inputs to a function?

While this approach works well for single inputs, what about multiple inputs?

Now the race runs through multiple stations: Seattle to San Francisco to Los Angeles to San Diego. We still need to determine the faster train for this route.

We can only measure times between adjacent stations.

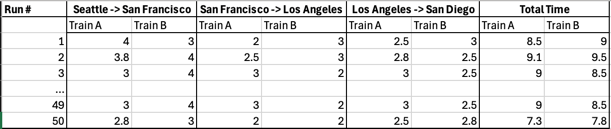

Here is how the timing data looks like (in hours):

With 300 data points (50 runs × 3 segments × 2 trains) and varying conditions on each segment, determining the faster train becomes even more challenging.

Which train is faster?

Our insight about measuring peak performance still applies, but we need to measure each segment separately since the track differs between segments due to hills and track curves.

We divide the route into segments between stations and measure each train's fastest time per segment. We find the minimum time for each segment, then sum these minimums to get the total route time. The train with the lowest sum of minimum times is fastest. This approach better captures each train's intrinsic speed because measuring shorter segments reduces the chance of encountering noise in that segment, compared to measuring the entire route. The result is more accurate timing data.

Codeflash applies this same principle to functions with multiple inputs. For workloads with multiple inputs, it measures a function's intrinsic speed on each input separately. The total intrinsic runtime is the sum of these individual minimums.

This approach proves highly accurate, even on noisy virtual machines. We use a 5% noise floor for runtime (10% on GitHub Actions) and only consider optimizations significant if they're at least 5% faster than the original function. This technique effectively minimizes measurement noise, giving us an accurate measure of a function's true, noise-free, intrinsic speed.